Don’t crucify me for what I’m about to write, but when I first heard The Doors 1967 debut album, I was underwhelmed. Part of the reason for this is I had heard “Light My Fire” a hundred thousand times (I might be exaggerating a tad) on rock radio. Although it’s a good song, it’s hard to be amazed by it in the same way in the 21st century.

Don’t hear me wrong. There are moments on The Door’s debut LP that are fascinating such as the concluding track “The End,” a nine-minute jazz odyssey with a spoken word section that’s rife with Oedipal undertones. But as a whole, when you look back from 2025 eyes, it’s hard to see the record as the same mind-blowing masterpiece it was back in the day. It also doesn’t help how the record, like many releases from the late ‘60s, have been immortalized in Baby Boomer nostalgia legend.

But there’s a deeper reason why hearing a studio album of The Doors doesn’t capture their essence. Countless people over the years have shared how impressive Jim Morrison and The Doors was to watch, how spellbinding the band’s performance could truly be.

You get a brief glimpse of it in their live albums such as Absolutely Live. When I heard the way Morrison interspersed his wild screams and patter with guitar noodling of Robby Krieger, well-timed yet loose drumming of John Densmore, and breathtaking musicianship of Ray Manzarek, I started to understand why those at the time found The Doors so stunning. Their live shows were a better representation of who they are and how they play.

This makes sense when you consider the music they take inspiration from. Although, yes, the music is classified as “rock,” there is a lot of jazz influence within their tunes. Many jazz fans know that the best recordings in this genre are often the live ones, as the energy of the crowd and the particular night influence each musician’s improvised solos more positively. It’s hard not to see why: the added pressure to “sink or swim” is where artists in this particular genre truly thrive.

However, I still felt I was missing something on Absolutely Live as I was still only hearing a live show. I needed to see it to truly understand.

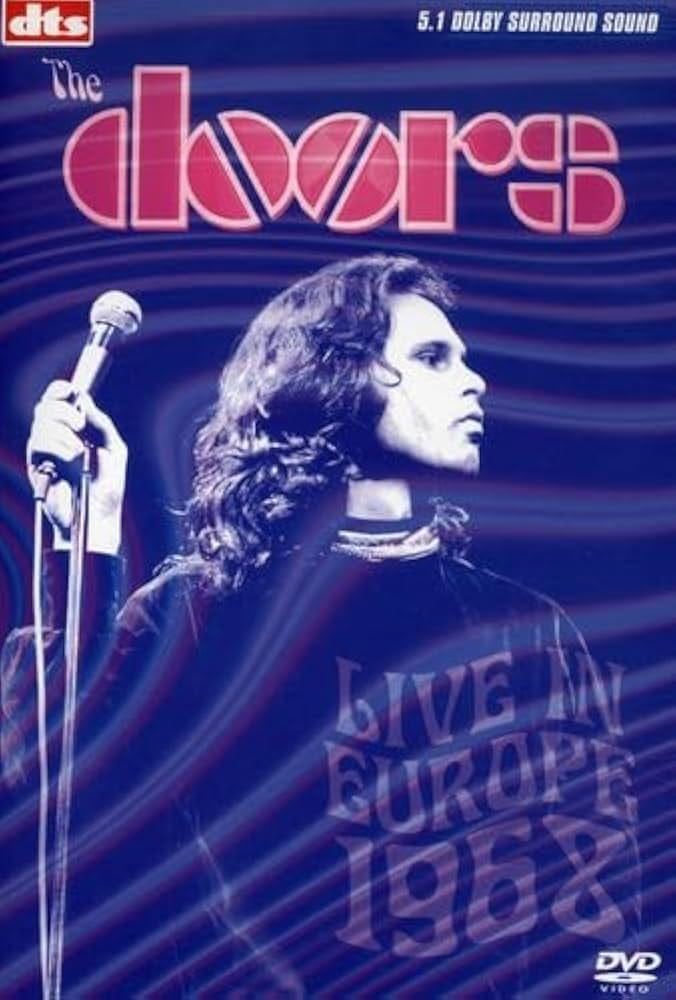

Thankfully, I now can say I had the opportunity to do so. A while ago, I was in a thrift store and found The Doors: Live in Europe 1968. For a couple bucks, I snatched it up. It ended up being a good buy, despite a few weird choices throughout the concert film.

But before I gripe, let me tell you the best parts:

Even though the concert footage is in black and white, when you see Jim Morrison stare into the cameras, you can finally understand his performative appeal. The man has an unearthly and hypnotizing presence with dark, moody eyes. When these mix with the gravelly nature of his bassy vocals, it’s hard to look away. Though sometimes the poetry of his lyrics becomes a little silly (in my opinion), he is aided by three incredible backing musicians who are all admirable in their own right.

The standout track in the film is “When The Music’s Over” with a lengthy jam session among all the musicians (including even wails from Morrison) that is stunning. Even though they are improvising throughout, there is a noticeable telepathy among all of them when they play.

There are many moments like this throughout the live portions of the film. What’s most interesting is not to hear the chorus of “Light My Fire,” but the strange, elongated breakdowns that will never be found in the studio album. They give you a sense of the improvisational nature of the group, and the abilities of what these four men were able to achieve every night they played.

If you were a careful reader of the above paragraph, you may have noticed I wrote “live portions of the film.” This is because in the beginning and randomly throughout Live in Europe, there are moments when Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick and Paul Kantner (who looks like he just woke up) talk about The Doors.

Though their commentary is sometimes insightful, it suffers because it undercuts The Doors’ performative material. Hearing about this legendary act and all the mythos surrounding it yet again (even though it’s from two musicians who performed on tour with them) feels performative, similar to Oliver Stone’s The Doors biopic. To each of Slick’s quips, there’s an underlying feeling: “Oh, man, it was the ‘60s. You had to be there…”

Sure, this nostalgia is fun to think about, and the interview clips may have made appealing “Special Features.” But to use them to, for example, jarringly introduce the film after a thirty-second clip of “Light My Fire” at the beginning feels like a sucker punch. Then to continually add them between every few songs, the mesmerizing appeal of The Doors’ performance is ruined.

Why? Well, the entire idea of a concert film like this is to be able to place yourself in 1968 and feel what it was like to experience the band at the time. Context here doesn’t help you because if you went to go see The Doors then, you only would have had word of mouth. Perhaps you read an article or heard their album. But you of course certainly wouldn’t have been reminded ad infinitum about how important the band is and why they matter in a retrospective manner.

Though The Doors is far from the only band to be mythologized, seeing this DVD made me think about band mythology and retrospectives more deeply. How much do we let people tell us what it was like instead of experiencing it ourselves? And can we even ever truly experience it watching TV in the same way as someone who was at The Whiskey A Go Go in 1968 did?

Of course not. But watching Live in Europe got me the closest to what it must have felt like (despite my gripes) and helped me understand what people see in The Doors. For that reason, it’s worth watching, especially if you’re a Doors skeptic like I was. It certainly made me want to dig deeper into the group and listen to more of their material (especially more of their live stuff).